Three years since it became law on April 1, 2010, it’s becoming increasingly clear this historic legislation was hastily drafted without proper evaluation of ground realities in primary education criminally neglected for over six decades. A close reading of the RTE Act indicates that several of its ill-conceived provisions have the potential to wreck India’s primary-secondary education. Dilip Thakore reports

Although for the public and Indian media march 31, 2013 was just another day and at best marked the end of the government’s and corporate India’s fiscal year, for the managements of India’s 1.30 million primary-secondary schools — specially for 80,000 private schools (220,000 according to government enumerators who count each section such as primary, upper primary and secondary within a school as separate units) — it was a day of reckoning. On the day a three-year time window given to schools to improve their infrastructure and teacher-pupil ratios and other norms as detailed in the Schedule of the historic Right to Free and Compulsory Education (aka RTE) Act, 2009 which became operational on April 1, 2010, slammed shut. With effect from April 1 this year, schools which haven’t upgraded their teacher-pupil ratios, buildings, toilets, drinking water facilities and playgrounds etc “shall” be derecognised and forcibly shut down by the competent authority (municipal and/or state government) under the provisions of s.19 of the Act.

Although for the public and Indian media march 31, 2013 was just another day and at best marked the end of the government’s and corporate India’s fiscal year, for the managements of India’s 1.30 million primary-secondary schools — specially for 80,000 private schools (220,000 according to government enumerators who count each section such as primary, upper primary and secondary within a school as separate units) — it was a day of reckoning. On the day a three-year time window given to schools to improve their infrastructure and teacher-pupil ratios and other norms as detailed in the Schedule of the historic Right to Free and Compulsory Education (aka RTE) Act, 2009 which became operational on April 1, 2010, slammed shut. With effect from April 1 this year, schools which haven’t upgraded their teacher-pupil ratios, buildings, toilets, drinking water facilities and playgrounds etc “shall” be derecognised and forcibly shut down by the competent authority (municipal and/or state government) under the provisions of s.19 of the Act.

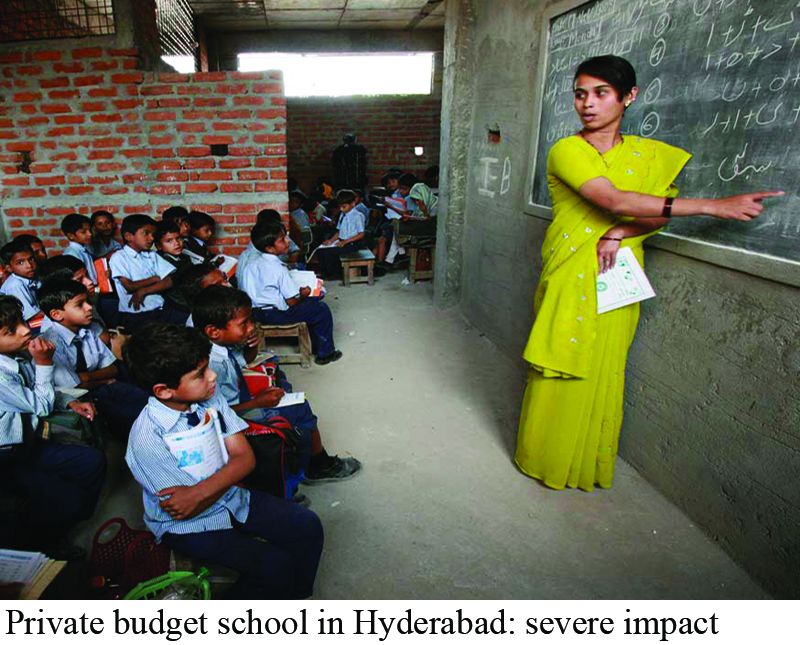

While the great majority of well-established private schools patronised by India’s 40 million middle and elite households exceed the infrastructure and other norms prescribed by the RTE Act Schedule, the closure of the facilities upgradation window on March 31 is likely to severely impact the country’s estimated 400,000 unrecog-nised private ‘budget’ schools which have unauthorisedly mushroomed countrywide over the past half century.

Sited mainly in the country’s prolifer-ating urban slums, tier II towns and even in tiny villages across the country, private budget schools are the response of small-time, for-profit education entrepreneurs to India’s poor quality government primaries characterised by crumbling infrastructure, multi-grade classrooms, chronic teacher absent-eeism, corporal punishment, English language aversion and poor learning outcomes. With a growing number of bottom-of-the-pyramid households countrywide having cottoned on that education (especially English language learning) is the passport to socio-economic upward mobility and are ready to pay for real primary/elementary education, entrepreneurs have been quick to step forward and offer modestly priced schooling to children from low-income but high aspiration households.

Unsurprisingly, for-profit private budget schools are as unacceptable to the government establishment as to Left intellectuals who dominate Indian academia. These lobbies are steadfast in their conviction that education cannot be “commercialised”, a nostrum sanct-ified by a generation of ideologically “committed” Supreme Court judges elevated to the bench by the populist socialist government of Mrs. Indira Gandhi in the 1970s. Although long-retired, the judges delivered a string of ideologically correct judgements out-lawing the commercialisation of education (but curiously, not of health, housing, food etc) which have become binding precedents for judges of the apex court.

Although the focus of these binding judgements has been professional (medicine, engineering), collegiate and higher education, they have provided sufficient ammunition to Left intellec-tuals to continuously (albeit unsuccess-fully) excoriate “elite” and even budget schools for commericalisation of education and profiteering. Typically, Left-socialist intellectuals schooled in Marxist gobbledygook economics and sociology, believe that capitalists — including budget school promoters — have unlimited resources from which they should provide education as charity. And undoubtedly mentally engaged with matters of higher import and greater substance, they have had little time or patience to research ways and means to raise teaching-learning standards in government schools. Moreover, although most of them are fluently English literate, they are averse to teaching English in government primaries, the main cause of the flight of the subaltern classes to private budget primaries countrywide.

But though left intellectuals prompted by populist former HRD minister Kapil Sibal — who drafted the RTE Act — are clearly hostile to private budget schools which parents from lowest income households prefer to dysfunctional government schools, the socio-economic value addition of private budget schools has been rigorously demonstrated by Dr. James Tooley, professor of education at Newcastle-Upon-Tyne University in his revealing book The Beautiful Tree — A Personal Journey into how the World’s Poorest People are Educating Themselves (2009). To research and gather material for this extraordinary work of scholarship which makes a strong case for special funding and microfinance being made available to private budget school promoters to enable them to upgrade their infra-structure, teacher-pupil ratios, pedag-ogies and facilities, Tooley visited slum schools around the world. He even takes on soft-Left Nobel Prize economist Dr. Amartya Sen for ignoring “the signi-ficance of his own evidence” which indicates that fed up with dysfunctional government schools, the poor are increasingly voting with their feet and wallets for private education. Unfortu-nately but typically, the establishment (media included) has ignored, if not suppressed, the inconvenient concl-usions of The Beautiful Tree.

Indeed, even though the Delhi-based voluntary organisation, Centre for Civil Society has initiated pilot projects —Delhi Voucher and School Vouchers for Girls — under which 800 government school children between ages 6-14 who have passed class I receive vouchers with an encashable (by CCS) value of Rs.4,000 to cover a year’s tuition fees in private budget schools of their choice in the national capital, the excellent results of this initiative have been brushed aside. On the contrary, the RTE imposes “totally unrealistic” conditions and cracks down harshly on private budget schools by prescribing “infra-structure norms, though desirable, take no notice of existing conditions,” according to Prof. J.S. Rajput, former director of the National Council for Teacher Education and National Council of Educational Research and Training, writing in the Sunday Express (April 14). Quite plainly, the intent of HRD ministry educrats who wrote the RTE Act, 2009 under the benign guidance of former Union minister Sibal, who was primarily interested in “hogging media space” and has since been transferred to the scams-tainted Union ministry for telecommunications and information technology, is to force children of the poor back into government schools where they cannot acquire more than hewing wood and drawing water skill-sets.

Four years on since the RTE Act, which belatedly made the State responsible for providing free and compulsory education to all children in the age group 6-14, was unanimously passed by Parliament, and three years since it became law on April 1, 2010, it’s becoming increasingly apparent this historic legislation was hastily drafted without proper evaluation of ground realities in primary education criminally neglected for over six decades. It’s also becoming apparent that the prime purpose and intent of the Act was to transfer part of the State’s burden of educating the masses to recognised private schools and shut down private budget schools, which have become an embarrassment to state and local government schools. Unfortunately for Indian education, the egalitarian blather which camouflages the political popu-lism — the curse of post-independence India — behind this reckless legislation has been swallowed hook, line and sinker by the mainstream media.

Indeed a close reading of the RTE Act indicates that several of its ill-conceived provisions have the potential to wreck primary-secondary education, and vitiate the few gains that India has made in school education since indepen-dence. The gains are few because for the past six decades, government (Central plus states) investment in developing human capital in a nation with the world’s largest child population has averaged 3.5 percent of GDP, against the global average of 4.4 percent and 6-8 percent in the industrial coun-tries of the developed world.

The pernicious s.19 which requires parents-chosen private budget schools to comply with the norms prescribed in the Schedule of the Act and “to fulfill such norms and standards at its own expenses” within the three-year window which closed on March 31 apart, there are several other provisions of the RTE Act which are likely to adversely impact school education countrywide. S.18 (1) which clearly has private budget schools in its sights, requires all non-government schools to obtain a recognition certificate from the local or state government, failing which they will not be allowed to conduct classes (s. 18(4)). School promoters who continue to dispense education without a recognition certificate are obliged to pay a fine of up to Rs.1 lakh and Rs.10,000 per day during which such contravention continues. Significantly, such recognition is mandatory only for schools “other than a school establi-shed, owned or controlled by the appropriate government”. Therefore, since government schools are not required to obtain a recognition certif-icate, it follows that they cannot be shut down under s. 19 if they fail to comply with the infrastructure and norms prescribed by the Schedule of the Act — a blatant inequity.

Although official recognition of primary and secondary schools is normative the world over, the peculiar ground conditions of Indian primary-secondary education have not been factored by the authors of the RTE Act who have conferred wide discretionary powers of recognition and certification upon notoriously corrupt local govern-ments and school inspectors who are certain to use them to extract rents and bribes. Even though the proviso to s.19 (2) ostensibly fetters the discretionary power of state and local government education inspectors by clearly stating that “no such recognition shall be granted to a school unless it fulfils the norms and standards prescribed under s. 19” (and the Schedule), this proviso doesn’t stipulate the consequences of partial fulfillment of the norms mandated by s. 19. Nor does it specify the final authority for adjudicating whether the norms have been fulfilled. “The provisions of ss.18 and 19 of the RTE Act, which confer wide discretionary powers upon education bureaucrats, are certain to make them very rich. Pastmasters of corruption, they will be in a unique position to extort bribes for real and imaginary infringement of s.19and Schedule provisions. The end result will be that private — including budget — school managements will be forced to raise tuition fees to factor in unofficial taxation,” says a senior retired Bang-alore-based educationist, who preferred to remain anonymous.

The draconian anti-poor provisions of s.19 apart, the other controversial provision of the RTE Act is s. 12(1) (c) which obliges all private schools to reserve 25 percent capacity of class I for poor children in their neighbourhood and provide them free education until class VIII. On behalf of EWS (economically weaker sections) children thus admitted, the State (i.e, the Central, state, local governments) are obliged to pay private school managements tuition fees equivalent to the per student expenditure incurred by the state government in its own schools. Unsurprisingly, the country’s high-end private schools built and carefully nurtured at great expense by promoters without financial aid or concessions from the State, challenged s. 12(1) (c) in the Supreme Court as violative of their fundamental right to “establish and administer education institutions of their choice” (Article 30(1) of the Constitution) as also of their right to “carry on any business, trade or profession” as provided by Article 19(1) (g).

The draconian anti-poor provisions of s.19 apart, the other controversial provision of the RTE Act is s. 12(1) (c) which obliges all private schools to reserve 25 percent capacity of class I for poor children in their neighbourhood and provide them free education until class VIII. On behalf of EWS (economically weaker sections) children thus admitted, the State (i.e, the Central, state, local governments) are obliged to pay private school managements tuition fees equivalent to the per student expenditure incurred by the state government in its own schools. Unsurprisingly, the country’s high-end private schools built and carefully nurtured at great expense by promoters without financial aid or concessions from the State, challenged s. 12(1) (c) in the Supreme Court as violative of their fundamental right to “establish and administer education institutions of their choice” (Article 30(1) of the Constitution) as also of their right to “carry on any business, trade or profession” as provided by Article 19(1) (g).

Delivering judgement on a clutch of writ petitions clubbed together under Society for Unaided Schools of Rajasthan vs. Union of India (Writ Petition (c) No. 95 of 2010) on April 12, 2012, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of s. 12 (1) (c) by a 2-1 majority inter alia on the ground that the RTE Act empowers the State to provide for free and compulsory education of children in the age group 6-14, not necessarily provide it directly. It also held that the quota for poor children residing in the neighbourhood of schools was a reasonable restriction of their promoters’ right to carry on the profession of education. However, making an important distinction which has frustrated the prime intent of the framers of the Act and generated considerable confusion within the educracy and the public, the bench exempted minority (and boarding) schools from applicability of s.12 (1) (c).

Quite evidently, the intent of then Union HRD minister Kapil Sibal and the educracy was to win the goodwill and favour of state-level politicians who control huge caste, communal and criminal vote banks, by allowing their children free entry into the country’s ‘convent’ or Christian missionary schools which teach in the much-prized English medium, or at least teach the English language seriously. But by exempting minority schools (without defining them) from having to reserve a 25 percent quota for poor children, the Supreme Court judgement set the proverbial cat among the pigeons, especially within the education bureaucracies of state governments.

Although a full year has elapsed after the Supreme Court upheld the validity of the RTE Act and s. 12(1) (c) in particular, there’s great confusion about the definition of minority schools. Several state governments including Karnataka have drafted Rules under the Act which dispute the traditional definition of minority schools as being institutions promoted by religious minorities. According to educrats in Karnataka, minority schools are instit-utions in which the majority of pupils are from the promoters’ community. There-fore they are demanding that only schools certified as minority institutions by the state government are exempt from admitting poor neighbourhood children. Moreover, to ensure that their own children can avail free-of-charge education in top-ranked private scho-ols, education bureaucrats have set the income ceiling for poor households at Rs.3.5 lakh per year, a definition described as ridiculous by the Karnataka high court.

“The RTE Act was hurriedly drafted by the former HRD minister with the prime intent of transferring 25 percent of the State’s burden of providing free and compulsory elementary education, to private schools. Now it has become clear that grabbing a 25 percent quota for poor children and simultaneously expanding government control over private schools was the hidden agenda of the RTE Act. The whole issue is a populist hoax because assuming 150,000 private schools admit ten children each year, the government fee reimbursement to private schools at an average Rs.10,000 per child will be Rs.1,500 crore. Over ten years the total payout will be Rs.15,000 crore for a mere 1.5 million children. This substantial amount could have been better utilised for upgrading the infrastructure of government schools. Moreover, the RTE Act discourages private investment in K-12 education. S. 12 (1) (c) is a populist vote-catching provision which doesn’t make any economic sense,” says Damodar Goyal, president of the Mumbai-based National Foundation for the Promotion and Protection of Private Education and chairman of the Society for Unaided Schools of Rajasthan.

“The RTE Act was hurriedly drafted by the former HRD minister with the prime intent of transferring 25 percent of the State’s burden of providing free and compulsory elementary education, to private schools. Now it has become clear that grabbing a 25 percent quota for poor children and simultaneously expanding government control over private schools was the hidden agenda of the RTE Act. The whole issue is a populist hoax because assuming 150,000 private schools admit ten children each year, the government fee reimbursement to private schools at an average Rs.10,000 per child will be Rs.1,500 crore. Over ten years the total payout will be Rs.15,000 crore for a mere 1.5 million children. This substantial amount could have been better utilised for upgrading the infrastructure of government schools. Moreover, the RTE Act discourages private investment in K-12 education. S. 12 (1) (c) is a populist vote-catching provision which doesn’t make any economic sense,” says Damodar Goyal, president of the Mumbai-based National Foundation for the Promotion and Protection of Private Education and chairman of the Society for Unaided Schools of Rajasthan.

There are several other provisions of the ill-conceived, mala fide and carelessly drafted RTE Act, 2009 which are bound to lower already rock-bottom standards in elementary education. For instance, s. 16 mandates that “no child admitted in a school shall be held back in any class or expelled from school till completion of elementary education”. According to a growing number of educationists countrywide, this provision is likely to make teachers’ control of classrooms more difficult, and is certain to drag down standards of secondary educ-ation as a huge cohort of untested and under-prepared children enter secondary education.

“This provision of the RTE Act is certain to depress already low learning outcomes in India’s school system. When children are assured of promotion without rigorous testing they are unlikely to invest serious effort in learning. The drafters of the RTE Act are obviously unaware that examinations and tests — and the power to deny promotion — are necessary for teachers to identify weak students and take remedial action. The no-detention mandate of the Act will lead to further deterioration of learning outcomes in elementary education, with large num-bers of under-prepared children entering secondary education, forcing down standards there. It’s a populist, retro-grade measure,” says J. Ajeeth Prasad Jain, senior principal of Bhavan’s Rajaji Vidyashram, Chennai (estb. 1977), ranked among the country’s Top 30 day schools in the EducationWorld India School Rankings 2012.

The opinion that s.16 will do more harm than good to India’s school education system, is endorsed by Vasudha Neel Mani, principal of the CIE(UK)-affiliated Vidya Sanskar International School, Faridabad (estb. 2006) and ranked among the country’s Top 25 international schools by EducationWorld. “Even if not by way of written examinations, testing children to assess learning outcomes is of vital importance. But this is impossible in crowded classrooms. In Indian condit-ions where teacher-pupil ratios are hugely adverse and classrooms have more than 24 children, the directive of s.16 in the RTE Act will greatly harm the school education system,” says Neel Mani, a psychology and education postgrad of Annamalai University, a former special needs educationist with teaching experience in several top-ranked schools including Pathways World School, Noida and Heritage, Gurgaon.

The opinion that s.16 will do more harm than good to India’s school education system, is endorsed by Vasudha Neel Mani, principal of the CIE(UK)-affiliated Vidya Sanskar International School, Faridabad (estb. 2006) and ranked among the country’s Top 25 international schools by EducationWorld. “Even if not by way of written examinations, testing children to assess learning outcomes is of vital importance. But this is impossible in crowded classrooms. In Indian condit-ions where teacher-pupil ratios are hugely adverse and classrooms have more than 24 children, the directive of s.16 in the RTE Act will greatly harm the school education system,” says Neel Mani, a psychology and education postgrad of Annamalai University, a former special needs educationist with teaching experience in several top-ranked schools including Pathways World School, Noida and Heritage, Gurgaon.

These ill-conceived provisions of the RTE Act rushed through Parliament in times when entire sessions were disrup-ted by the irresponsible opposition BJP aside, state governments which are empowered to frame Rules to implement the Act within their jurisdictions have shown half-hearted interest, because they are obliged to bear 25 percent of the expense of implementing the legislation. Moreover, their educrats have been quick to subvert the intent of the Act by framing rules to either avail free-of-charge superior private school education for their own offspring, or maximise rent extraction opportunities.

For instance in the southern state of Karnataka which was once reputed for its excellent education institutions and administration, corruption and rents extraction in school education are rampant. Block education officers (BEO) are blatantly certifying ineligible house-holds as ‘poor’ for a price, and subs-equently arm-twisting minority schools to admit children from certified households under the s. 12 (1) (c) quota.

Moreover, private school manage-ments have little faith in the capability or willingness of bankrupt state govern-ments to reimburse the modest tuition fees payable to private schools for poor children admitted under s. 12 (1) (c). One of the major grievances of KUSMA (Karnataka Unaided School Manage-ments Association) is that the reimbur-sement fees due to member schools for the academic year 2011-12 have not yet been paid.

The swirling chaos created by the poorly drafted RTE Act has disillusioned many knowledgeable education activists working towards a fair deal for children from bottom-of-the-pyramid households stuck in dysfunctional government schools notorious for teacher truancy and abysmal learning outcomes, for whom the tiny window of opportunity presented by private budget schools is set to be closed. “The inputs focus of the RTE Act indicates that its prime objective was to develop infrastructurend create employment, rather than improve the learning outcomes of primary students. Because of this inputs emphasis of the Act, more than 400,000 private budget schools are facing closure and the right of an estimated 20-30 million children to education of their choice is likely to be snatched away. It’s still not too late for state governments to shift the inputs focus of the RTE Act, with outcomes-based recognition of private budget schools. The state of Gujarat has framed Rules to this effect. This offers a smart, long-term policy solution,” opines Shantanu Gupta, associate director of the Advocacy Schools Choice Campaign of the Delhi-based Centre for Civil Society, India’s top-ranked think tank.

towards a fair deal for children from bottom-of-the-pyramid households stuck in dysfunctional government schools notorious for teacher truancy and abysmal learning outcomes, for whom the tiny window of opportunity presented by private budget schools is set to be closed. “The inputs focus of the RTE Act indicates that its prime objective was to develop infrastructurend create employment, rather than improve the learning outcomes of primary students. Because of this inputs emphasis of the Act, more than 400,000 private budget schools are facing closure and the right of an estimated 20-30 million children to education of their choice is likely to be snatched away. It’s still not too late for state governments to shift the inputs focus of the RTE Act, with outcomes-based recognition of private budget schools. The state of Gujarat has framed Rules to this effect. This offers a smart, long-term policy solution,” opines Shantanu Gupta, associate director of the Advocacy Schools Choice Campaign of the Delhi-based Centre for Civil Society, India’s top-ranked think tank.

Yet despite the numerous contrad-ictions and infirmities of the RTE Act which have generated confusion and dissonance within school education, informed academics and educationists believe it is well-intentioned legislation whose prime virtue is that it has focused public attention on all-important elementary education. “The RTE Act is not a failure; it’s a work in progress. During the th ree years since it became law, it has significantly increased Central and state government education budgets, provoked major teacher education reform debates and significantly increased the GER (gross enrollment ratio) in primary education. But while some progress is evident, much remains to be done with several studies including Pratham’s Annual Status of Education Report 2012 indicating that students’ learning attainments are poor and falling. There’s also a lot of work to be done in terms of better implementation of the RTE Act. Major institutional reform is required in critical areas such as teacher education and classroom processes, strengthened monitoring and quality assurance systems. Moreover, improved targeting of resources to reach the most deprived and marginalised children should become a paramount objective,” says Dr. Ashima Goyal, an alumna of the Delhi School of Economics and Bombay University, and currently professor of economics at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai.

ree years since it became law, it has significantly increased Central and state government education budgets, provoked major teacher education reform debates and significantly increased the GER (gross enrollment ratio) in primary education. But while some progress is evident, much remains to be done with several studies including Pratham’s Annual Status of Education Report 2012 indicating that students’ learning attainments are poor and falling. There’s also a lot of work to be done in terms of better implementation of the RTE Act. Major institutional reform is required in critical areas such as teacher education and classroom processes, strengthened monitoring and quality assurance systems. Moreover, improved targeting of resources to reach the most deprived and marginalised children should become a paramount objective,” says Dr. Ashima Goyal, an alumna of the Delhi School of Economics and Bombay University, and currently professor of economics at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai.

Likewise Shailendra Sharma, the Delhi-based programme director (central resources) of the Pratham Education Foundation, cautions against “sweeping generalisations” about the landmark RTE Act. “Universal access, retention and learning have been — and remain — challenging tasks in primary and elementary education. The RTE Act addresses these issues. Over the past decade and particularly during the past three years since the RTE Act became operational, significant progress has been made in terms of infrastructure development and access in most states of the Union. This has created the environment and opportunity to focus on issues related to improved learning outcomes,” says Sharma, an alumnus of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai who has over a decade’s experience of field work in elementary education.

cautions against “sweeping generalisations” about the landmark RTE Act. “Universal access, retention and learning have been — and remain — challenging tasks in primary and elementary education. The RTE Act addresses these issues. Over the past decade and particularly during the past three years since the RTE Act became operational, significant progress has been made in terms of infrastructure development and access in most states of the Union. This has created the environment and opportunity to focus on issues related to improved learning outcomes,” says Sharma, an alumnus of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai who has over a decade’s experience of field work in elementary education.

The consensus of informed opinion is that despite its suspect motivations, careless drafting, licence-permit-quota raj characteristics and inputs rather than outcomes focus, the RTE Act is a pointer in the right direction and worth saving. “The RTE Act undoubtedly has major flaws. It neglects children in the critical 0-6 and 15-18 age groups and despite the tokenism of s.12 (1) (c), it actually encourages the promotion of expensive private schools without insisting upon the Kendriya Vidyalaya model for government schools. However for the first time ever, s.19 has laid down minimum infrastructure norms for all schools — government schools incl-uded — to follow. Even though government schools cannot be shut down for not adhering to s.19 and Schedule norms, government will be forced by the SMCs (school manag-ement committees) constituted under the Act and public opinion to apply them to government schools. Despite its flaws which can be corrected by amendment, the RTE Act is shaping into a powerful tool for civil society to transform government schools and establish a common school system,” says Dr. Niranjan Aradhya, director of the Centre for Child and the Law at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore.

But even though it’s hazardous to contradict the considered opinion and cautious optimism of education experts, one can’t help feeling there’s an element of wishful thinking, tolerance of tokenism and glacial gradualism within the community of educationists inclined to discern a silver lining to the RTE Act, 2009. The threat of massive shakedown, if not closure, confronting the country’s estimated 400,000 private budget schools is immediate, and in the short run their students may well be forced back into non-performing government schools which are under no compulsion to reform in a hurry. Moreover, even as learning outcomes in primary education are steadily declining, the RTE Act has abolished exams in elementary educ-ation and mandates a no-detention policy, while the inclusive intent of s. 12 (1) (c) has been diluted by the Supreme Court and is being sabotaged by state government educracies.

But even though it’s hazardous to contradict the considered opinion and cautious optimism of education experts, one can’t help feeling there’s an element of wishful thinking, tolerance of tokenism and glacial gradualism within the community of educationists inclined to discern a silver lining to the RTE Act, 2009. The threat of massive shakedown, if not closure, confronting the country’s estimated 400,000 private budget schools is immediate, and in the short run their students may well be forced back into non-performing government schools which are under no compulsion to reform in a hurry. Moreover, even as learning outcomes in primary education are steadily declining, the RTE Act has abolished exams in elementary educ-ation and mandates a no-detention policy, while the inclusive intent of s. 12 (1) (c) has been diluted by the Supreme Court and is being sabotaged by state government educracies.

In the circumstances, action to amend the Act and clarify its confusing provi-sions is urgently required and cannot await the crystallisation of gradual people’s movements. And unfortunately the new ‘dream team’ of the Union HRD ministry — Union minister Dr. Pallam Raju and ministers of state Shashi Tharoor and Jitin Prasada — seems to be sulking in their tent and in no hurry to fortify the well-intentioned yet ineff-ective RTE Act, which is floundering in a sea of confusion.

With Hemalatha Raghupathi (Chennai); Praveer Sinha (Mumbai), Autar Nehru & Urmila Rao (Delhi)